Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Monday, December 05, 2005

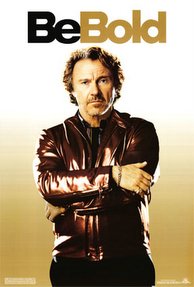

Harvey Keitel: garrulous, gruff … and cuddly? The consummate tough guy looks inward

Interview, March, 2005 by Eve Ensler

Whenever Harvey Keitel appears onscreen, growling at his adversaries with his trademark inflection, you can be certain that their luck is about to run out. But that tough-guy persona is ripe for comedic manipulation, which is just what happens to it in Keitel's new movie, Be Cool. A follow-up to Get Shorty (1995), the film co-stars Uma Thurman, Vince Vaughn, and John Travolta, who reprises his role as gangster-turned-movie mogul Chili Palmer. This time he's muscling his way into the music business, and Keitel plays Nick Car, the ruthless talent manager standing in his way. Keitel recently sat down with his close friend, playwright and women's advocate Eve Ensler, to discuss his most recent project and how his infamous macho schtick may just be, well, acting.

EVE ENSLER: So here I am with Harvey Keitel, one of my favorite people. Harvey, why don't you start by telling me what you're most excited about in your life?

HARVEY KEITEL: Well, that's a question that if I really answered would take me a couple of weeks. Of course, I'm terribly excited about my new son and about the revelations I'm having and the understandings I'm gaining.

EE: Anything specific you're thinking of?

HK: They have to do with childhood wounds and understanding where they come from, like the difficulty I've had with speaking.

EE: Give a specific example of a wound you're talking about.

HK: Well, I will not let anyone tell my son not to cry. I don't want anything to interfere with his expressing what he's feeling. As a kid I was told to shush, and as a result it's taken me a lifetime to be able to speak.

EE: What impact did not having space for that in your childhood have on you?

HK: I had to hide it--you hammer it down until you can't think anymore, you can't speak anymore, and your inner world is in retreat. You can't function, and you stutter, which I did as a boy. You will stutter not only vocally, but inwardly. You will hesitate, you will fumble, you will futz, and you will deny the truth because the truth is too difficult to handle. It's hard to select which situations to run away from once you become a runner, so you hide from everything.

EE: What's it like to play tough guys--guys who are playing through their hiddenness?

HK: You can only play through your hiddenness to the degree that you can live it. So to play a tough guy is to get in touch with what a tough guy or a tough woman within one's self is.

EE: So, if you had a vision of your son, what would he be like as a young man?

HK: He will know that he can feel whatever he is feeling, and it will be the right thing. And then he will learn to make choices.

EE: This must be a really healing experience for you, having a son.

HK: It's great. My wife keeps saying, "That's you as a little boy in your mother's arms."

EE: Talk about this new movie of yours, Be Cool. Why were you drawn to it?

HK: Hey, to be cool, baby! [laughs]

EE: Was there something in the script that you were particularly drawn to?

HK: My character was written as a very funny, active guy. He was coming from everywhere-doing this, doing that, just to make a buck. He was very superficial. I wanted to play that, to dance that. And that was quite simply a good reason for me to take the part; it presented a way to begin coming out of my shell. It was a good character to latch onto because it helped me to be at play with myself.

EE: Some people I was with recently were talking about sexy movies, and The Piano [1993] came up as most women's all-time favorite sexy movie, with you being the epitome of the sexy man. Why do you think that was such a sexy movie?

HK: It begins with the film's author and director, Jane Campion. The woman is a goddess. The environment she creates in and out of her films is one you want to be in. It's just lovely. And then Holly Hunter--she's another extraordinary lady. I mean, the talent that woman has! She's just a volcano. I used to take her and Jodie Foster as role models for my daughter, Stella.

EE: Do you watch that movie once in a while?

HK: I'll tell you, I watched it once.

EE: How'd you feel about your performance?

HK: [laughs] I loved the movie, which is why I never saw it again. It was just too perfect for me. Every wish I had to be in a great film and in an important story was fulfilled in The Piano.

EE: How many times has that happened in your career?

HK: I've been very lucky, to be perfectly honest. I've been in a number of incredible films.

EE: Where did you grow up?

HK: In Brooklyn.

EE: Was it a difficult childhood?

HK: Yeah, very. We were very poor. We lived in a two-flight walk-up above a Chinese laundry, which later became a grocery store. We shared a bathroom and a kitchen with two elderly women on our floor. A number of times it was difficult for my parents to pay the rent, so I knew what it was like to be broke and the effect that poverty can have on a family.

EE: Did you dream of acting?

HK: I always fantasized that I'd make a lot of money and take care of my mother.

EE: And were you able to do that?

HK: A little bit. She died too soon.

EE: What made you want to act?

HK: Well, who hasn't played dress-up as a child? I don't know why it carries on in some people and not in others. After I came out of the Marines I was searching for what to do with my life. I became a court stenographer, which I wasn't very fulfilled by, and I was selling shoes part-time. Once this young girl suggested that I come down and try acting. But I didn't, of course, because I was too shy. And then a fellow employee said to me, "You want to go see about acting lessons?" and I said okay. I'll never forget walking up the stairs of that building; it was on 5th Avenue, between 22nd and 23rd, and the staircase was tilted. I remember saying, "We've got to get out of here. This building is going to fall down." It was the Anthony Mannino Studio--he was a fairly well-known acting teacher in those days--but the building was really like a slum. My friend ended up leaving, and I stayed. But I went about it very slowly; I was scared to admit to my friends in Brooklyn that I was taking acting classes.

EE: I imagine admitting that would be hard.

HK: Yeah, and I didn't know if I could do it or not. I went up and studied a few times a week, and then about four years later, I began to get further into it and wanted to take lessons more often. One summer I went away to summer stock, and I committed myself to acting then.

EE: And at that point you knew?

HK: Well, I was going to try my best. It was dreadful, though. Forget working--you couldn't even get an agent to help you get work. But I just loved the people I met. They were so wonderful, courageous, fun, and persevering, and they were smarter than hell. They helped me break out of my macho stance.

EE: Was that hard?

HK: Very. I'll tell you how that happened. I used to take acting classes with this great teacher named Frank Corsaro, and afterwards we'd all go out for drinks. Now, the Vietnam War was just beginning at that time, and the entire group was against it except me, the former marine. I used to say all those things that an ignorant, closed-minded guy would say, like "Just send the Marines in, and they'll straighten this out." And they'd scream at me, "Harvey, what is wrong with you?" And I'd say, "What's the matter with you? You want the world to become Communist?" not even knowing what a Communist was [Ensler laughs]. Then one day, one of them handed me The Arrogance of Power by J. William Fulbright. After that I became a demonstrator against the war.

EE: What's so amazing about you is not only your seeking spirit but your willingness to be transformed by the world. Where do you think that comes from?

HK: I don't know--it's the luck of the dice, I guess.

EE: One thing people don't know about you is how extraordinarily supportive you are of young artists, particularly young filmmakers, and how many you've actually been behind at the beginning of their careers--people like Quentin Tarantino, Jane Campion, Tony Bui, Martin Scorsese. What do you attribute your ability to sniff out that kind of talent to?

HK: I don't know why or how, but I do recognize that I have it. I get a little glimmer of something in someone, and the glimmer I get is rawness. I like what's raw. I like to walk down alleys. In the Marine Corps I enjoyed being out in the wilderness, not knowing what's coming before you.

EE: So it's about being drawn to what's fresh and raw?

HK: Yes, things that have some truth to them.

EE: So, what's it been like for you to live in and out of Hollywood, which is seemingly a world with a lot of lies?

HK: Hollywood is comprised of many worlds, and the Hollywood commercial world is one of them; and in that world people tend to flock together, though with perhaps less of an eye towards contributing something to humankind than some of the others. Not many people are willing to give up their Mercedes.

EE: What would it take for people to want the inner life more than the outer life?

HK: Courage to strike out for something meaningful. But the only way you can really do that is to risk poverty, to risk not being popular.

EE: So what's something that you think people don't know about you? I for one know that you're a vagina-friendly man and were wildly supportive of The Vagina Monologues.

HK: Well, your play opened me up in ways that cataclysmic events tend to open someone up to truths previously unforeseen. To me, there is no difference between your Vagina Monologues and my dick; it's all about how we perceive ourselves. And that's what you did with The Vagina Monologues--you opened us up to another perception. I can't think of anything else. Do you know something about me that I don't?

EE: I think people have the idea that you are a real tough guy, but I know you to be a very tender person. That was shocking to me when I first met you. Another thing I know about you is that when you find a book you like, you send it to every person you know.

HK: That's how we met. When I saw The Vagina Monologues I tried to get my hands on as many copies of the book as I could.

EE: [laughs] I know! So what books are you obsessed with now?

HK: The Speech of the Grail by Linda Sussman and Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth and Art by Lewis Hyde.

EE: What's your vision for the next stage of your life?

HK: I'd like to take stories in the realm of mythology, the Bible, and anthropology and find a form for them in the cinema and the theater. For me, they denote a deeper truth about things. I'm sick of the politicians, and I don't just mean the American ones. I'm sick of this other nonsense--these people who, in the name of religion, teach their children to hate other children because of their religious beliefs. Neither the Western God nor Allah is telling them to kill the children of other people in the name of God.

EE: I think this is great. Is there anything else you want to say?

HK: Yeah. Can we erase this whole thing and do a different interview?

EE: Nope.

Eve Ensler recently performed her new play, The Good Body (Villard Books), on Broadway. Her most recent work, Vagina Warriors, is just out from Bulfinch.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Brant Publications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group

Whenever Harvey Keitel appears onscreen, growling at his adversaries with his trademark inflection, you can be certain that their luck is about to run out. But that tough-guy persona is ripe for comedic manipulation, which is just what happens to it in Keitel's new movie, Be Cool. A follow-up to Get Shorty (1995), the film co-stars Uma Thurman, Vince Vaughn, and John Travolta, who reprises his role as gangster-turned-movie mogul Chili Palmer. This time he's muscling his way into the music business, and Keitel plays Nick Car, the ruthless talent manager standing in his way. Keitel recently sat down with his close friend, playwright and women's advocate Eve Ensler, to discuss his most recent project and how his infamous macho schtick may just be, well, acting.

EVE ENSLER: So here I am with Harvey Keitel, one of my favorite people. Harvey, why don't you start by telling me what you're most excited about in your life?

HARVEY KEITEL: Well, that's a question that if I really answered would take me a couple of weeks. Of course, I'm terribly excited about my new son and about the revelations I'm having and the understandings I'm gaining.

EE: Anything specific you're thinking of?

HK: They have to do with childhood wounds and understanding where they come from, like the difficulty I've had with speaking.

EE: Give a specific example of a wound you're talking about.

HK: Well, I will not let anyone tell my son not to cry. I don't want anything to interfere with his expressing what he's feeling. As a kid I was told to shush, and as a result it's taken me a lifetime to be able to speak.

EE: What impact did not having space for that in your childhood have on you?

HK: I had to hide it--you hammer it down until you can't think anymore, you can't speak anymore, and your inner world is in retreat. You can't function, and you stutter, which I did as a boy. You will stutter not only vocally, but inwardly. You will hesitate, you will fumble, you will futz, and you will deny the truth because the truth is too difficult to handle. It's hard to select which situations to run away from once you become a runner, so you hide from everything.

EE: What's it like to play tough guys--guys who are playing through their hiddenness?

HK: You can only play through your hiddenness to the degree that you can live it. So to play a tough guy is to get in touch with what a tough guy or a tough woman within one's self is.

EE: So, if you had a vision of your son, what would he be like as a young man?

HK: He will know that he can feel whatever he is feeling, and it will be the right thing. And then he will learn to make choices.

EE: This must be a really healing experience for you, having a son.

HK: It's great. My wife keeps saying, "That's you as a little boy in your mother's arms."

EE: Talk about this new movie of yours, Be Cool. Why were you drawn to it?

HK: Hey, to be cool, baby! [laughs]

EE: Was there something in the script that you were particularly drawn to?

HK: My character was written as a very funny, active guy. He was coming from everywhere-doing this, doing that, just to make a buck. He was very superficial. I wanted to play that, to dance that. And that was quite simply a good reason for me to take the part; it presented a way to begin coming out of my shell. It was a good character to latch onto because it helped me to be at play with myself.

EE: Some people I was with recently were talking about sexy movies, and The Piano [1993] came up as most women's all-time favorite sexy movie, with you being the epitome of the sexy man. Why do you think that was such a sexy movie?

HK: It begins with the film's author and director, Jane Campion. The woman is a goddess. The environment she creates in and out of her films is one you want to be in. It's just lovely. And then Holly Hunter--she's another extraordinary lady. I mean, the talent that woman has! She's just a volcano. I used to take her and Jodie Foster as role models for my daughter, Stella.

EE: Do you watch that movie once in a while?

HK: I'll tell you, I watched it once.

EE: How'd you feel about your performance?

HK: [laughs] I loved the movie, which is why I never saw it again. It was just too perfect for me. Every wish I had to be in a great film and in an important story was fulfilled in The Piano.

EE: How many times has that happened in your career?

HK: I've been very lucky, to be perfectly honest. I've been in a number of incredible films.

EE: Where did you grow up?

HK: In Brooklyn.

EE: Was it a difficult childhood?

HK: Yeah, very. We were very poor. We lived in a two-flight walk-up above a Chinese laundry, which later became a grocery store. We shared a bathroom and a kitchen with two elderly women on our floor. A number of times it was difficult for my parents to pay the rent, so I knew what it was like to be broke and the effect that poverty can have on a family.

EE: Did you dream of acting?

HK: I always fantasized that I'd make a lot of money and take care of my mother.

EE: And were you able to do that?

HK: A little bit. She died too soon.

EE: What made you want to act?

HK: Well, who hasn't played dress-up as a child? I don't know why it carries on in some people and not in others. After I came out of the Marines I was searching for what to do with my life. I became a court stenographer, which I wasn't very fulfilled by, and I was selling shoes part-time. Once this young girl suggested that I come down and try acting. But I didn't, of course, because I was too shy. And then a fellow employee said to me, "You want to go see about acting lessons?" and I said okay. I'll never forget walking up the stairs of that building; it was on 5th Avenue, between 22nd and 23rd, and the staircase was tilted. I remember saying, "We've got to get out of here. This building is going to fall down." It was the Anthony Mannino Studio--he was a fairly well-known acting teacher in those days--but the building was really like a slum. My friend ended up leaving, and I stayed. But I went about it very slowly; I was scared to admit to my friends in Brooklyn that I was taking acting classes.

EE: I imagine admitting that would be hard.

HK: Yeah, and I didn't know if I could do it or not. I went up and studied a few times a week, and then about four years later, I began to get further into it and wanted to take lessons more often. One summer I went away to summer stock, and I committed myself to acting then.

EE: And at that point you knew?

HK: Well, I was going to try my best. It was dreadful, though. Forget working--you couldn't even get an agent to help you get work. But I just loved the people I met. They were so wonderful, courageous, fun, and persevering, and they were smarter than hell. They helped me break out of my macho stance.

EE: Was that hard?

HK: Very. I'll tell you how that happened. I used to take acting classes with this great teacher named Frank Corsaro, and afterwards we'd all go out for drinks. Now, the Vietnam War was just beginning at that time, and the entire group was against it except me, the former marine. I used to say all those things that an ignorant, closed-minded guy would say, like "Just send the Marines in, and they'll straighten this out." And they'd scream at me, "Harvey, what is wrong with you?" And I'd say, "What's the matter with you? You want the world to become Communist?" not even knowing what a Communist was [Ensler laughs]. Then one day, one of them handed me The Arrogance of Power by J. William Fulbright. After that I became a demonstrator against the war.

EE: What's so amazing about you is not only your seeking spirit but your willingness to be transformed by the world. Where do you think that comes from?

HK: I don't know--it's the luck of the dice, I guess.

EE: One thing people don't know about you is how extraordinarily supportive you are of young artists, particularly young filmmakers, and how many you've actually been behind at the beginning of their careers--people like Quentin Tarantino, Jane Campion, Tony Bui, Martin Scorsese. What do you attribute your ability to sniff out that kind of talent to?

HK: I don't know why or how, but I do recognize that I have it. I get a little glimmer of something in someone, and the glimmer I get is rawness. I like what's raw. I like to walk down alleys. In the Marine Corps I enjoyed being out in the wilderness, not knowing what's coming before you.

EE: So it's about being drawn to what's fresh and raw?

HK: Yes, things that have some truth to them.

EE: So, what's it been like for you to live in and out of Hollywood, which is seemingly a world with a lot of lies?

HK: Hollywood is comprised of many worlds, and the Hollywood commercial world is one of them; and in that world people tend to flock together, though with perhaps less of an eye towards contributing something to humankind than some of the others. Not many people are willing to give up their Mercedes.

EE: What would it take for people to want the inner life more than the outer life?

HK: Courage to strike out for something meaningful. But the only way you can really do that is to risk poverty, to risk not being popular.

EE: So what's something that you think people don't know about you? I for one know that you're a vagina-friendly man and were wildly supportive of The Vagina Monologues.

HK: Well, your play opened me up in ways that cataclysmic events tend to open someone up to truths previously unforeseen. To me, there is no difference between your Vagina Monologues and my dick; it's all about how we perceive ourselves. And that's what you did with The Vagina Monologues--you opened us up to another perception. I can't think of anything else. Do you know something about me that I don't?

EE: I think people have the idea that you are a real tough guy, but I know you to be a very tender person. That was shocking to me when I first met you. Another thing I know about you is that when you find a book you like, you send it to every person you know.

HK: That's how we met. When I saw The Vagina Monologues I tried to get my hands on as many copies of the book as I could.

EE: [laughs] I know! So what books are you obsessed with now?

HK: The Speech of the Grail by Linda Sussman and Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth and Art by Lewis Hyde.

EE: What's your vision for the next stage of your life?

HK: I'd like to take stories in the realm of mythology, the Bible, and anthropology and find a form for them in the cinema and the theater. For me, they denote a deeper truth about things. I'm sick of the politicians, and I don't just mean the American ones. I'm sick of this other nonsense--these people who, in the name of religion, teach their children to hate other children because of their religious beliefs. Neither the Western God nor Allah is telling them to kill the children of other people in the name of God.

EE: I think this is great. Is there anything else you want to say?

HK: Yeah. Can we erase this whole thing and do a different interview?

EE: Nope.

Eve Ensler recently performed her new play, The Good Body (Villard Books), on Broadway. Her most recent work, Vagina Warriors, is just out from Bulfinch.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Brant Publications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group